Zooarchaeology, the study of animal remains from archaeological sites, has a significant contribution to studies of Paleolithic human subsistence, behavior and environment. Zooarchaeological research is complemented with taphonomic studies, which reconstruct the depositional history of the faunal assemblage and provide insights into site formation processes, past economic structures and subsistence strategies.

To date, only a few Early Middle Paleolithic bone assemblages from the Levant underwent a detailed taphonomic and zooarchaeological analysis. The rarity of well-preserved faunal assemblages dating to the Early Middle Paleolithic highlights the importance of the faunal remains recovered in the Misliya Cave excavations. By studying in detail the systematically recovered assemblage we were able to reconstruct its taphonomic history and human subsistence behavior at the site, namely mode of prey acquisition, prey transport patterns and food processing habits. To date, three faunal assemblages from Misliya Cave have been studied: a sample from the cemented sediments of the upper terrace (Bar-Oz et al. 2004), another sample from the cemented sediment column in square L15 (in preparation), and a comprehensive study of the "Soft Area" (squares I-N\9-10 in the upper terrace) faunal assemblage (Yeshurun 2006, Yeshurun et al. in press).

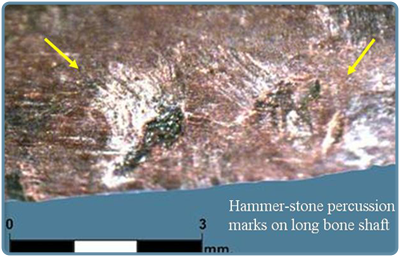

The research protocol included the identification of maximum number of skeletal elements (including limb shaft fragments), the determination of ungulate mortality patterns, and the systematic documentation of bone surface modifications and mode of bone fragmentation.

![]()

|

|

|

Aurochs |

Fallow Deer |

Gazelle |

|

|

|

Red Deer |

Roe Deer |

Turtles |

|

|

|

Wild Boar |

Ostrich |

Wild Goat |

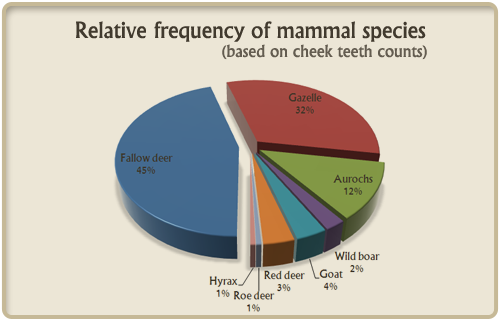

The Misliya Cave "soft area" faunal assemblage is overwhelmingly dominated by ungulate taxa. The most common prey species is the Mesopotamian fallow deer (Dama mesopotamica), mostly prime-aged individuals, followed closely by the mountain gazelle (Gazella gazella). Some aurochs (Bos primigenius) remains are also found. Other ungulate species, represented only by a few specimens each, are wild boar (Sus scrofa), red deer (Cervus elaphus), roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) and wild goat (Capra sp.). Small game remains are rare and are represented by several bones of hare-sized mammals, tortoise (Testudo graeca), and chuckar partridge (Alectoris chuckar). Also present are several small pieces of ostrich (Struthio camelus) egg- shell fragments. Carnivore remains are entirely absent. Species diversity in Misliya Cave reflects the existence of various environmental niches in the vicinity of the cave; deer species occupy wooded areas, while gazelle and aurochs occupy open landscape, and ostrich is associated with flat, open savannas.

shell fragments. Carnivore remains are entirely absent. Species diversity in Misliya Cave reflects the existence of various environmental niches in the vicinity of the cave; deer species occupy wooded areas, while gazelle and aurochs occupy open landscape, and ostrich is associated with flat, open savannas.

Multivariate taphonomic analysis of the "soft area" assemblage demonstrated that:

- The assemblage was created solely by humans occupying the cave; carnivores played virtually no role in the creation and modification of the assemblage.

- The faunal assemblage is characterized by significant density-mediated biases. The primary cause of bone damage is related to human activities, including butchery, bone marrow extraction, burning and possibly trampling. Post-depositional bone damage resulted mainly from root etching and possibly sediment compaction.

- Fallow deer (medium ungulate) remains suffered greater fragmentation than gazelle (small ungulate) remains, possibly because of their larger size and surface area. This phenomenon does not appear to be linked to any differential human treatment of fallow deer and gazelle carcasses.

- Gazelle carcasses were transported complete to the site, while fallow deer carcasses underwent some field butchery. This is supported by both skeletal element profiles and butchery mark data.

- The burning patterns observed in the assemblage most likely represent human activities at the site, notably meat roasting and discarding bone into hearths.

|

|

|

|

The new zooarchaeological data from Misliya Cave, in particular the abundance of meat-bearing limb bones displaying filleting cut-marks and the acquisition of prime-age prey, demonstrate that Early Middle Paleolithic people acquired their prey by active and systematic hunting in various environmental settings in the vicinity of the cave. Thus, modern large-game hunting, carcass transport and meat processing behaviors were already established in the Levant in the Early Middle Palaeolithic, more than 200 ka ago.

- Bar-Oz G., M. Weinstein-Evron, P. Livne and Y. Zaidner 2004. Fragments of information: preliminary taphonomic results from the Middle Palaeolithic breccia layers of Misliya Cave, Mount Carmel, Israel. In: T. O’Connor (Ed.). Biosphere to Lithosphere: New Studies in Vertebrate Taphonomy. Oxbow Press, Oxford, pp. 128-136.

- Yeshurun R. 2006. Mousterian Faunal Remains from Misliya Cave, Mount Carmel: Taphonomy, Paleoeconomy and Paleoecology. Unpublished MA Thesis, University of Haifa (Hebrew).

- Yeshurun R., G. Bar-Oz and M. Weinstein-Evron 2006. The Palaeoecology of Misliya Cave, an Early Middle Palaeolithic site in Mount Carmel. Israel Journal of Ecology and Evolution 52: 202-203 (Abstract)

- Yeshurun R., G. Bar-Oz and M. Weinstein-Evron in press. Modern hunting behavior in the early Middle Paleolithic: Faunal remains from Misliya Cave, Mount Carmel, Israel. Journal of Human Evolution. Available online August 1, 2007.